Simon Macdonald writes:

Although her Letters survive, and a lot can be traced about her life history elsewhere in the archives, we have no portrait of the duchess of Elbeuf. In the eighteenth century, pseudo-scientific theories were emerging which linked the shape of the face to character, intelligence, and so on — and the links (or not) between beauty and virtue were an endless subject for poets. Our interest is born of a simpler curiosity: we’d like to put a face to the name!

Portrait pictures from the eighteenth century abound. But not every French grandee from the period was desperately keen to have their traits immortalized for posterity. Our duchess seems to have been more interested in books than in pictures. In the Letters, she comments occasionally on what she is reading, but she never mentions anything about images. Maybe she just did not like having her picture taken? Curiouser still, while she had a huge house in central Paris, and it is possible to reconstruct a lot of its contents, her art collection remains something of an enigma. Indeed, we do not even know whether she had one at all.

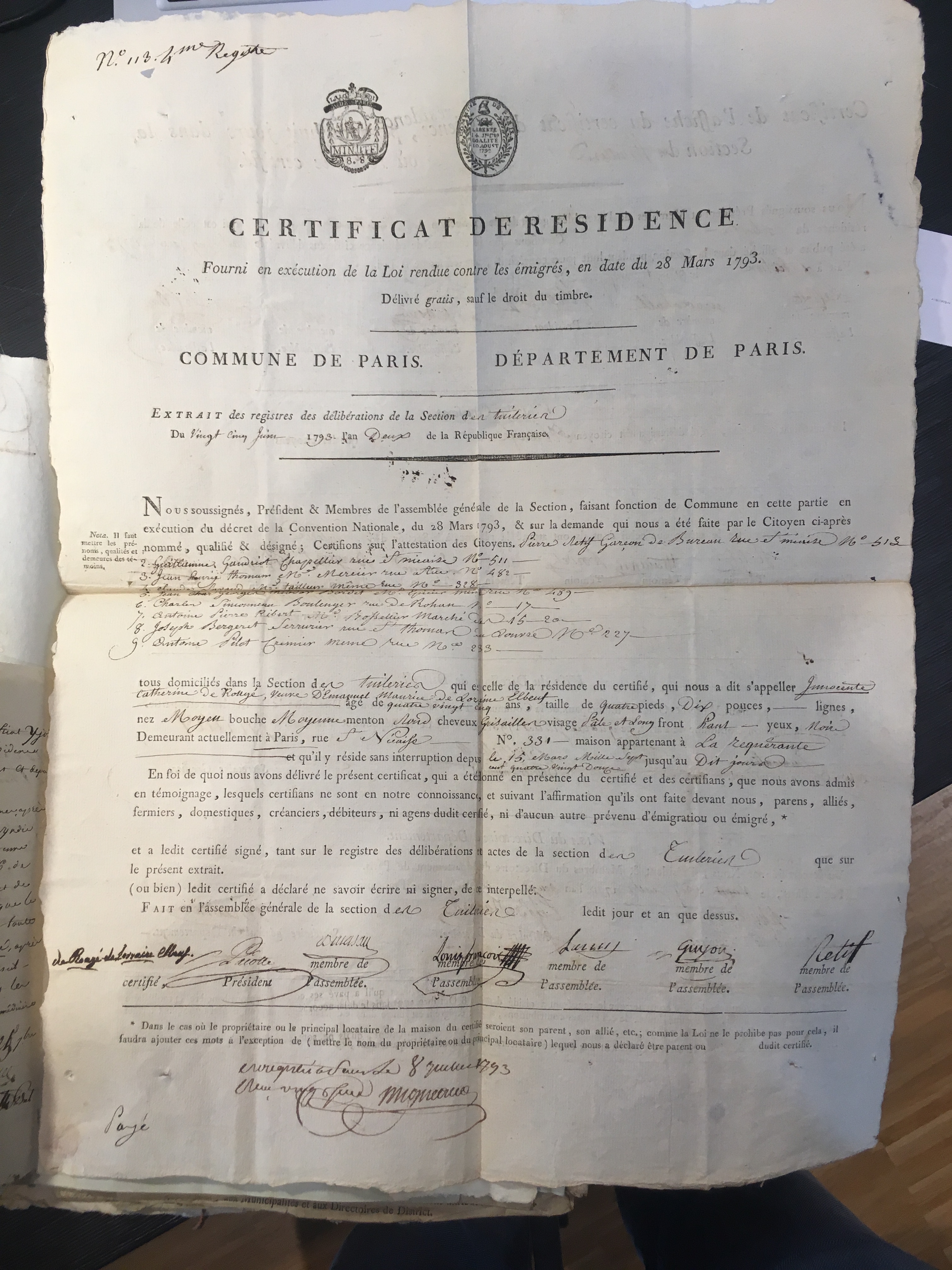

Fortunately for us, we do have some other accounts of the duchess which give us some sense of what she looked like. We owe a lot of our information here to the revolutionary bureaucracy. For the eighteenth century, and the period after 1789 in France especially, saw a race to develop what we would now call identity documents. Passports, early forms of identity card, certificates attesting to residence, the list goes on: both the Old Regime monarchy, and the new regime of the Revolution even more so, were concerned to track people in movement, and to find ways of pinning them down. (The French historian Vincent Denis has written a wonderful book all about this, called Une histoire de l’identité. France, 1715–1815, published in 2008.) It so happens that, for our duchess, a number of these ‘identity’ documents survive. And thanks to them it is possible to glean some inkling of her appearance.

AN F7 5708 Residency certificate for the duchess of Elbeuf (25 June 1793). Her signature can be seen bottom left.

According to one such document (right), written up in the final summer of her life by the local revolutionary authorities, at the age of 85 her height was ‘quatre pieds, dix pouces’, or roughly four foot ten inches. French measurements and English measurements were not exactly the same, but she was clearly no giant. Then follow a series of other descriptors, some of them more helpful than others. Her nose was described as moyen (‘average’, or ‘normal’), as was her mouth. She had a ‘round’ chin, and ‘grey’ hair (grisaille). Her face was ‘pale and long’ with a ‘big’ (haut) forehead. And she had black eyes.

It’s not much to go on, but it gives us at least a kind of pen portrait of our writer. She was a little old lady. From the Letters, we know that behind her ‘big’ forehead lay a very lively intelligence, notwithstanding her very advanced years.