Now for the full transcription and English translation of the start of the duchess’ letter from her country estate in Moreuil. It is the end of August 1790 and it seems that her family retreat is no longer a sanctuary from the revolutionary turmoil she has been reporting on from Paris and elsewhere across the country…

Now for the full transcription and English translation of the start of the duchess’ letter from her country estate in Moreuil. It is the end of August 1790 and it seems that her family retreat is no longer a sanctuary from the revolutionary turmoil she has been reporting on from Paris and elsewhere across the country…

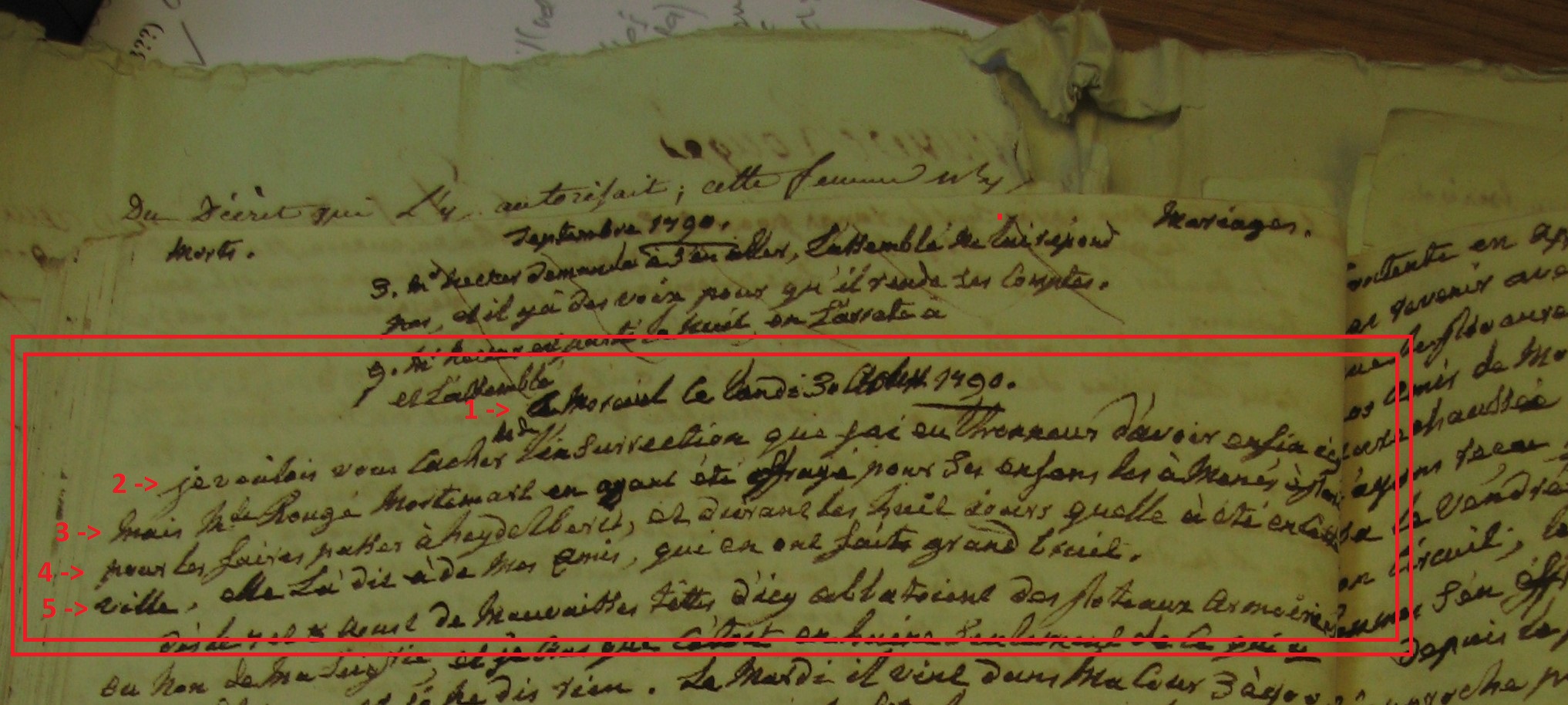

Line 1: A Moreuil ce lundi 30 aoust 1790

Line 2: Je voûlois vous cacher [[inserted interline word]Mde] l’insurrection que j ai eu honneur d’avoir enfin icy,

Line 3: mais Mde Rougé Mortemart en ayant été effrayé pour ses enfans les à menés à Paris

Line 4: pour les faires passer à Heydelberet [Heidelberg] , et durant les huit iours qu elle à été en cette

Line 5: ville, elle l à dit à de mes amis, qui en ont fait grand bruit.

Words in [bold] are editorial comment.

Translation:

Moreuil. Monday 30 August 1790

I wanted to conceal from you, Madame, the insurrection which I had the honour of finally hosting here, but it made Madame Rougé Mortemart so terrified for her children that she took them to Paris in a bid to get them to Heidelberg, and while she was in the city for eight days she told my friends about it and this created something of a sensation.

Madame Rougé Mortemart was Victurienne-Delphine-Natalie de Rougé, marquise de Rougé. She was a relation of the duchess (the wife of her deceased first cousin once removed), and Simon will be writing a post shortly about Elisabath Vigée Le Brun’s celebrated portrait featuring Madame Rougé and her children (two boys). She is not mentioned previously in the Moreuil section of the Letters so it is unclear how long she has been staying there, but we know that the duchess took a close interest in this part of her extended family — not least because, in the absence of any children herself, Madame Rougé’s eldest son stood to inherit the major part of the duchess’ property.

The ‘insurrection’ which had so terrified Madame Rougé (but apparently not the defiant duchess) took place earlier in August. It had begun with attacks on the wooden posts used to Continue reading