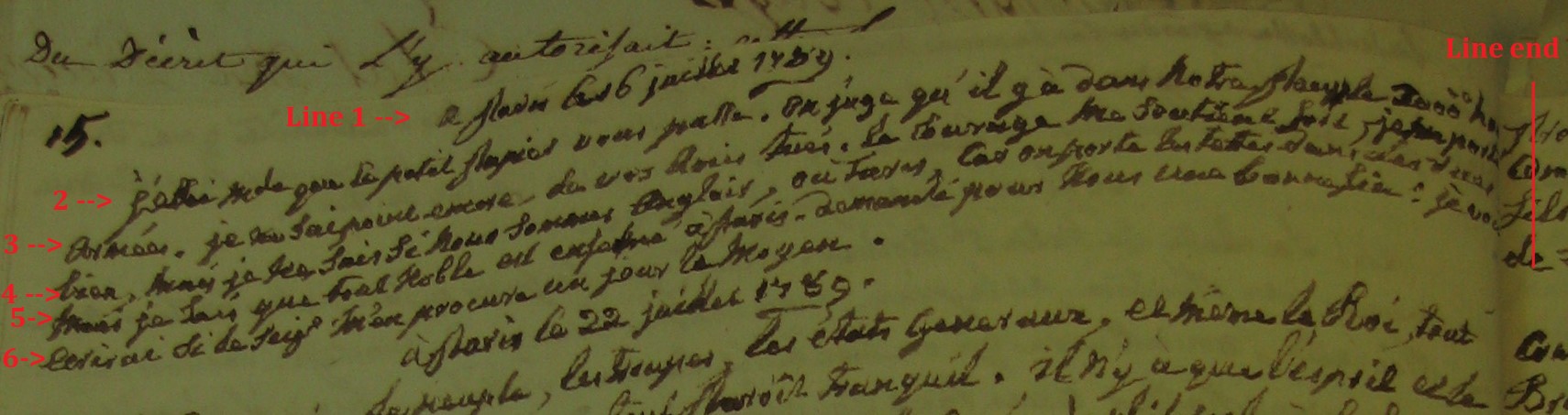

In this ‘Decipher the duchess’ series of posts we are working through the entry for 16 July 1789, in which the duchess provides a description of conditions in Paris in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Bastille two days earlier. Here is the relevant section of the manuscript again, with lines added for guidance:

And below is our own completed transcription. Remember, [square brackets] indicate a questionable or assumed reading of the manuscript by the Project team.

Line 1: A Paris ce 16 juillet 1789.

Line 2: J’[essai] Mde que ce petit Papier vous passe. On juge qu’il y à dans notre Peuple [300000] hom.

Line 3: armées. je ne sai point encore, de vos Amis tués. Le courage me soutient fort, je me porte

Line 4: bien, mais je ne sais si nous sommes Anglois, ou Turcs, car on porte les tettes dans les rues,

Line 5: mais je sais que tout noble est enfermé à Paris. demandé pour nous une bonne fin! je vous

Line 6: ecrirai si le seigr m’en procure un jour le Moyen.

We are also translating a substantial part of the Letters as part of the project (there will be an update about this on the blog in the near future). Here is our English version of this entry:

Paris 16 July 1789

I am trying to get this note to you, Madame. They estimate that there are 300000 armed men in amongst the people of the city. I still have no news about your friends who have been killed. Courage sustains me greatly. I myself am well, but I do not know if we have all turned into the English or the Turks, given that heads are being carried through the streets. What I do know is that anyone who is a noble is trapped in Paris. Pray we get a happy ending! I will write to you if one day the Lord grants me the means to do so.

This is an atmospheric snapshot of revolutionary Paris just two days after the collapse of royal authority witnessed by its inhabitants when the Bastille prison was stormed. The heads ‘carried through the streets’ are a reference to the notorious treatment of the marquis de Launay, who had surrendered as the governor of the Bastille, and the city’s chief magistrate, Jacques de Flesselles. They were hacked to death in the street later that day, and their heads then paraded around on pikes – including very near to the hôtel d’Elbeuf.

Detail from anonymous engraving, ‘La Journée mémorable du mardi 14 juillet 1789′ (1789) showing the heads of Governor de Launay and the magistrate de Flesselles being paraded in front of the town hall, only a few hundred metres from the duchess’ own residence. Image available via Gallica, the digital hub for the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The figure of 300,000 armed men is pretty unbelievable (the entire population of the capital in 1789 has been estimated at just over half a million), but this exaggeration is an understandable reaction to the scale of upheaval in recent days. Prior to the attack on the Bastille protestors had commandeered over 30,000 firearms from government stocks held at the Invalides military veterans’ hospital, and crowds numbering into the thousands had been roaming the streets since news of the sacking of a popular minister, Jacques Necker, had reached the capital on the 12th. Thomas Jefferson, reporting to U.S. Secretary of Foreign Affairs, John Jay, in his capacity as Minister to France just three days after the duchess penned her entry, described how in the build-up to the 14th, ‘the people now armed themselves with such weapons as they could find in armourer’s shops and private houses, and with bludgeons, and were roaming all night through parts of the city’.[1] Indeed, everything was happening on a scale that must have been bewildering to the duchess and many other eyewitnesses: within twenty-four hours of the storming of the Bastille an enterprising construction engineer named Pierre-François Palloy had got eight hundred men on site for its immediate demolition.[2] The duchess’ presentation of the nobility’s unique situation within this revolutionary ferment is consistent with her traditional view of French society. She and her fellow nobles were supposed to form a distinct, privileged class near the apex of this structure, but this position was being rapidly undermined: the Paris authorities did indeed immediately forbid nobles from leaving the city amid growing suspicions that their class had been and continued to plot against the Revolution. Trust in aristocratic commitment to the revolutionary cause continued to deteriorate to the point where nobility itself was abolished by the National Assembly on 19 June 1790.

[1] Letter from Thomas Jefferson to John Jay (19 July 1789). Jefferson also estimated a crowd of 60,000 lined the streets for the King’s journey into Paris from Versailles on 17 July, giving another indication of the scale of popular participation in the unfolding political revolution.

[2] Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (1989), p. 411.