Now for the full transcription and English translation of the start of the duchess’ letter from her country estate in Moreuil. It is the end of August 1790 and it seems that her family retreat is no longer a sanctuary from the revolutionary turmoil she has been reporting on from Paris and elsewhere across the country…

Now for the full transcription and English translation of the start of the duchess’ letter from her country estate in Moreuil. It is the end of August 1790 and it seems that her family retreat is no longer a sanctuary from the revolutionary turmoil she has been reporting on from Paris and elsewhere across the country…

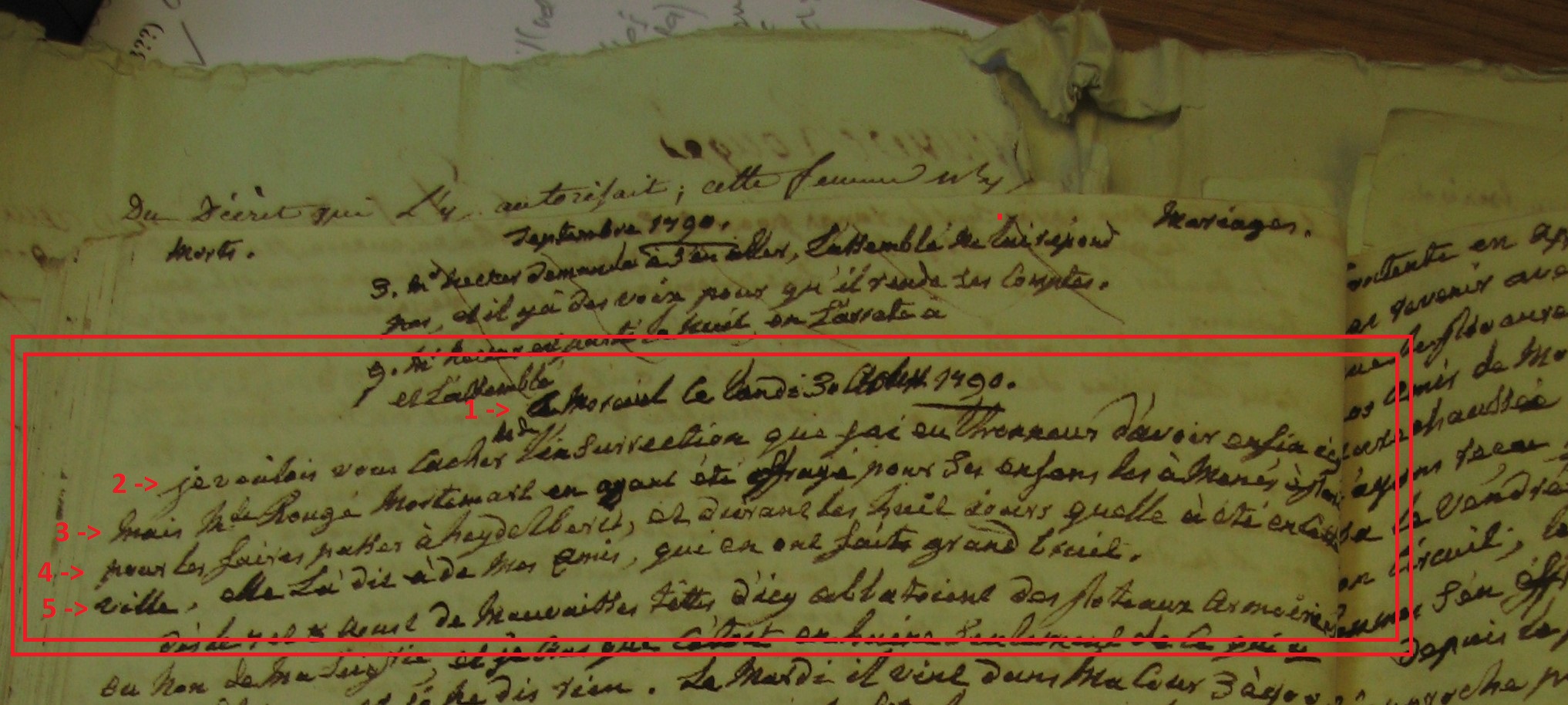

Line 1: A Moreuil ce lundi 30 aoust 1790

Line 2: Je voûlois vous cacher [[inserted interline word]Mde] l’insurrection que j ai eu honneur d’avoir enfin icy,

Line 3: mais Mde Rougé Mortemart en ayant été effrayé pour ses enfans les à menés à Paris

Line 4: pour les faires passer à Heydelberet [Heidelberg] , et durant les huit iours qu elle à été en cette

Line 5: ville, elle l à dit à de mes amis, qui en ont fait grand bruit.

Words in [bold] are editorial comment.

Translation:

Moreuil. Monday 30 August 1790

I wanted to conceal from you, Madame, the insurrection which I had the honour of finally hosting here, but it made Madame Rougé Mortemart so terrified for her children that she took them to Paris in a bid to get them to Heidelberg, and while she was in the city for eight days she told my friends about it and this created something of a sensation.

Madame Rougé Mortemart was Victurienne-Delphine-Natalie de Rougé, marquise de Rougé. She was a relation of the duchess (the wife of her deceased first cousin once removed), and Simon will be writing a post shortly about Elisabath Vigée Le Brun’s celebrated portrait featuring Madame Rougé and her children (two boys). She is not mentioned previously in the Moreuil section of the Letters so it is unclear how long she has been staying there, but we know that the duchess took a close interest in this part of her extended family — not least because, in the absence of any children herself, Madame Rougé’s eldest son stood to inherit the major part of the duchess’ property.

The ‘insurrection’ which had so terrified Madame Rougé (but apparently not the defiant duchess) took place earlier in August. It had begun with attacks on the wooden posts used to mark out the duchess’ land, attacks which were probably encouraged by the National Assembly’s abolition of nobility back in June.[1] That legislation had banned the public display of coats of arms but also anticipated broader attacks on public and private noble ephemera and tried to prohibit such public disorder. At Moreuil as elsewhere over the summer of 1790, this attempt at a curated abolition of nobility, a central pillar of French society, had generated considerable instability. The duchess’ letter presents the attacks on her boundary markers (some of which may have been decorated with her coat of arms) as the trigger for several days of confrontation with a crowd of several hundred locals. Various demands were made for changes in the way the duchess ran her extensive estate (including the local mills which would have been central to the local economy) and her estate manager was threatened with the noose. As the situation deteriorated, the duchess claimed that her own life was also threatened. The danger only ebbed away after she had made a defiant speech scolding the crowd for the ingratitude they were showing to their ageing benefactor, and she subsequently coordinated with local and national authorities to discourage any further disorder.

The tone on display in this extract is noteworthy: the duchess presents herself as controlled and defiant, in contrast to the nervous Madame Rougé and the excitable gossiping of her social circle in the capital. This extract is also of interest for the clue it might give about the identity of the ‘Madame’ the duchess is purportedly writing to: she claims to have wanted to keep the news from her (meaning that she must live some distance away) but can no longer do so once Madame Rougé has spread the news among her Parisian friends – with whom ‘Madame’ must also therefore have had connections.

An extended extract of this letter is being translated for this project, and will be made available as part of the translation resource at a later date. The identity of ‘Madame’, and the question of whether this manuscript is a copy of a real correspondence or a feigned ‘letters’ series, are still being investigated by the project team. Further updates on these issues will be provided on this blog.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

[1] The French text of this law can be read in the context of all the other legislation passed in 1790 thanks to a digitised collection of National Assembly’s laws (printed contemporaneously by the Assembly’s approved printer François-Jean Baudouin): https://collection-baudouin.univ-paris1.fr/.