Simon Macdonald writes:

A previous blog entry here noted that we don’t have any portrait of the duchess of Elbeuf, and we don’t even know for sure whether she had an art collection as such. Maybe she just didn’t much like paintings? Eighteenth-century France was full of art-historically significant names — Jean Siméon Chardin’s still lifes, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s portraits, Jacques-Louis David’s history paintings. But that doesn’t mean that everyone at the time was enamoured of the fruits of the palette.

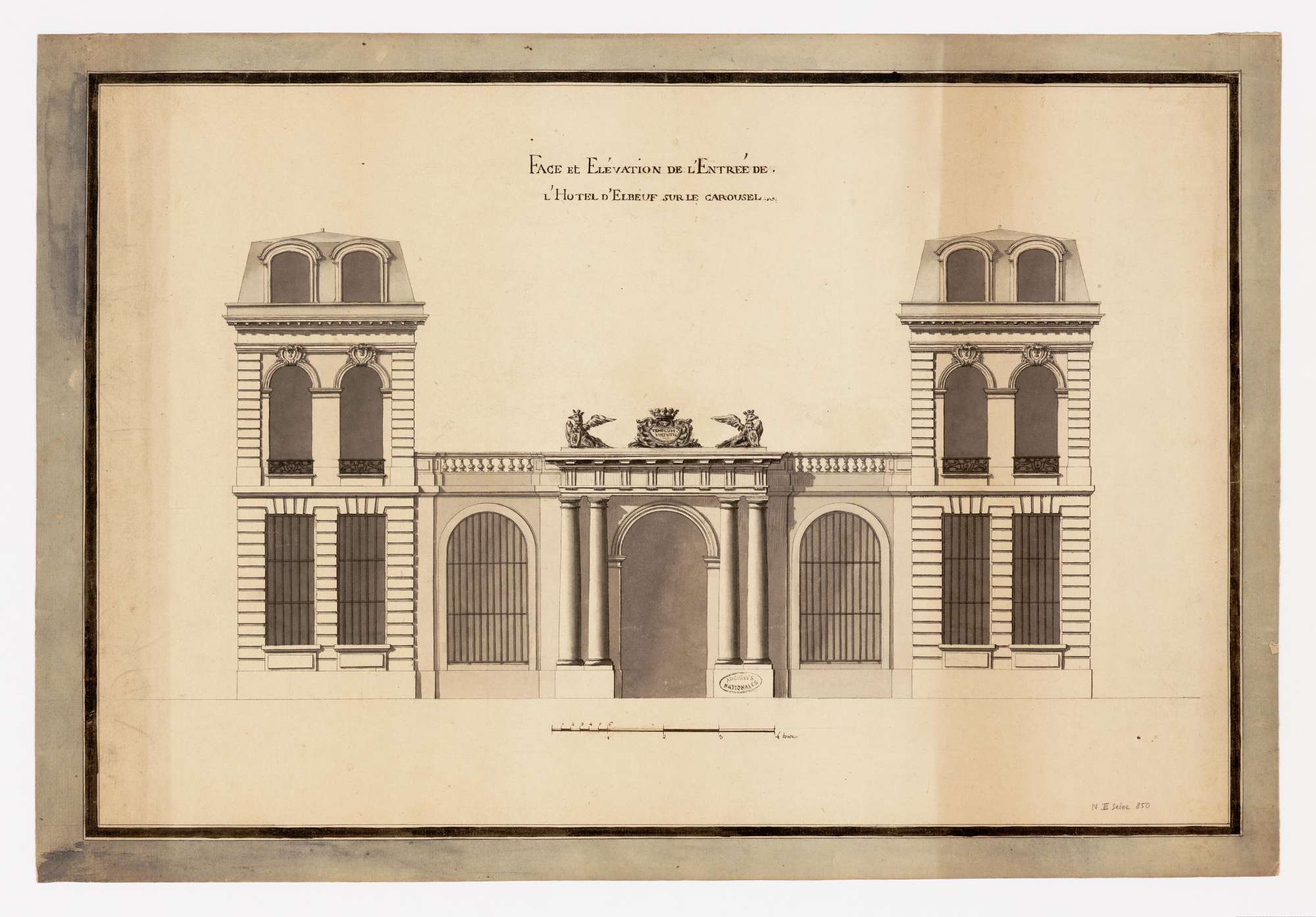

Still, we know she had a huge house in central Paris (see below). And, with so much wall space to fill, it seems unlikely that she had absolutely no pictures on them. In fact, we know quite a lot about the things she owned at the time of her death because more or less all her property then passed into the hands of the government.

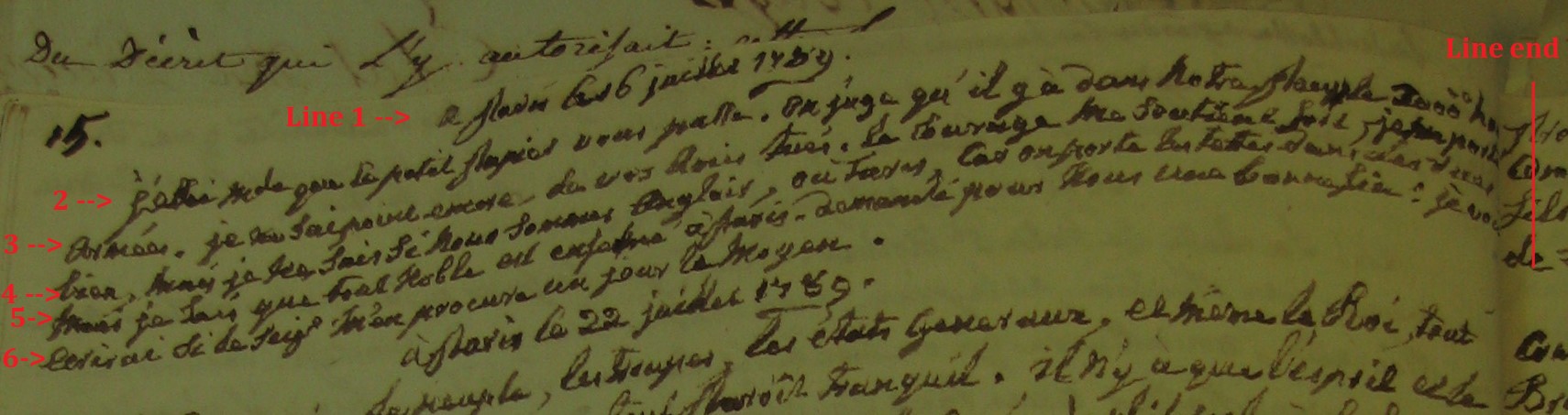

Property confiscated by the revolutionary state, or which passed to the state by other kinds of forfeiture or sequestration, was carefully documented, with a view to finding items of value. That ‘value’ could come in the form of information. For example, a diary such as the kept by the duchess might hold secrets which could be politically useful to the regime. For that reason, officials felt it was worth reading — and worth retaining in the state archives. But mostly ‘value’ meant monetizable assets. This included real estate, investments, furniture, and indeed just about any kind of bric-a-brac which might attract a buyer at auction. Occasionally, particularly rare or valuable artefacts might be deemed sufficiently important to be turned into museum items — today’s Louvre Museum, for instance, is full of things like this — or to be placed in public libraries.

Photo © Hydar Dewachi

Photo © Hydar Dewachi