We are delighted to announce that our new book, The Letters of the duchesse d’Elbeuf: hostile witness to the French Revolution is out now in the Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment series (Liverpool University Press). You can purchase a copy here.

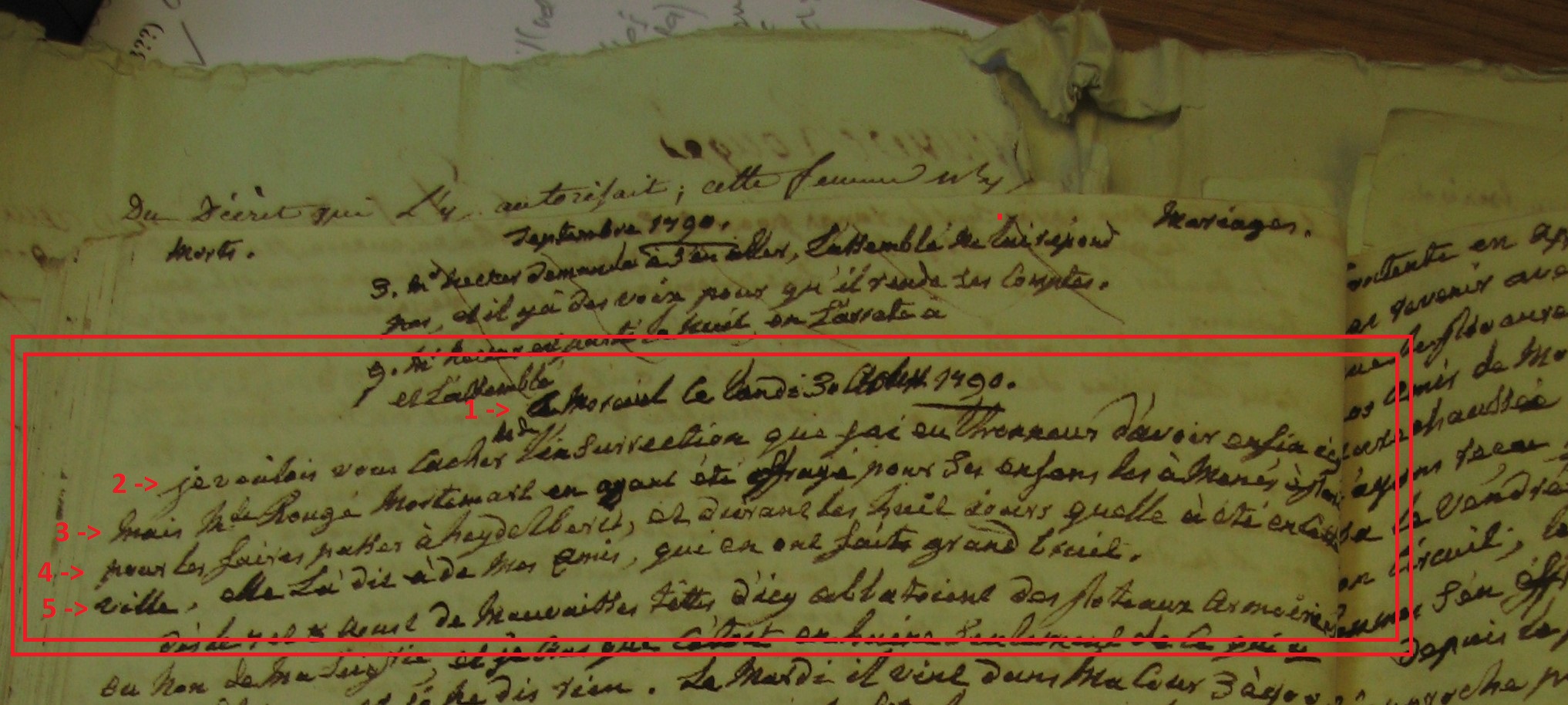

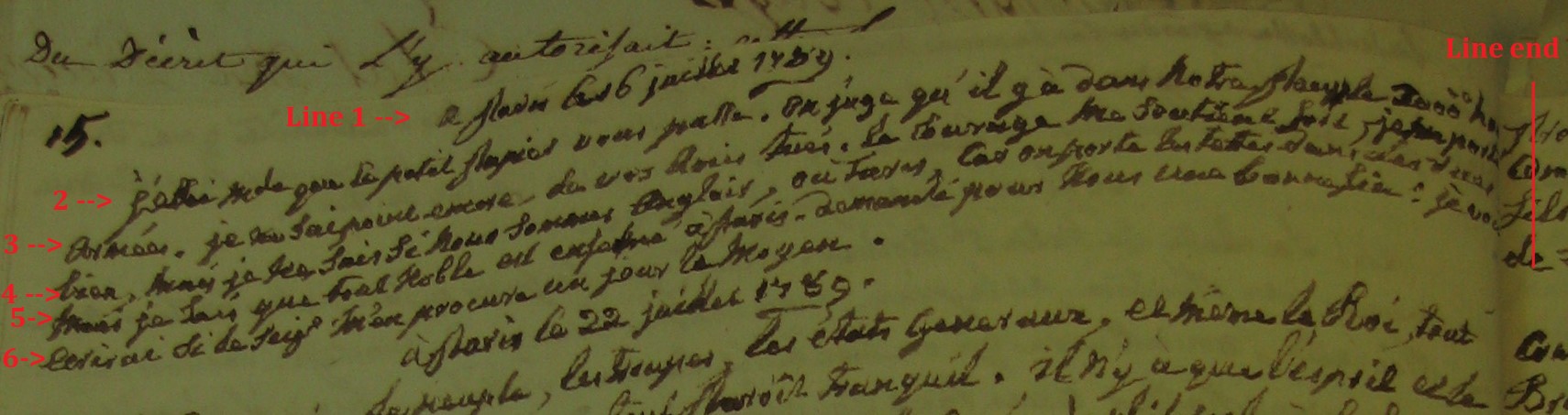

This co-edited scholarly edition features a full transcription of six notebooks confiscated by the revolutionary authorities in early 1794 and filled with about 75,000 words in the scrawled hand of the duchess of Elbeuf. Her hostile, unique testimony covers the period December 1788 through to January 1794.

The octogenarian duchess was one of France’s richest women at the outbreak of the Revolution, and our book’s extended introduction fixes scholarly attention on her for the first time. We unpick her earlier life via a range of other archival material (twenty earlier notebooks did not survive their transfer into the possession of the state) before offering an extended study of the Revolutionary process through her testimony. The introduction also sets the Letters in the wider context of eighteenth-century epistolary culture and life-writing.

And remember: all this is complemented by our free, public digital resource of translated extracts from the same Letters. Enjoy!

—Colin Jones, Simon Macdonald, Alex Fairfax-Cholmeley